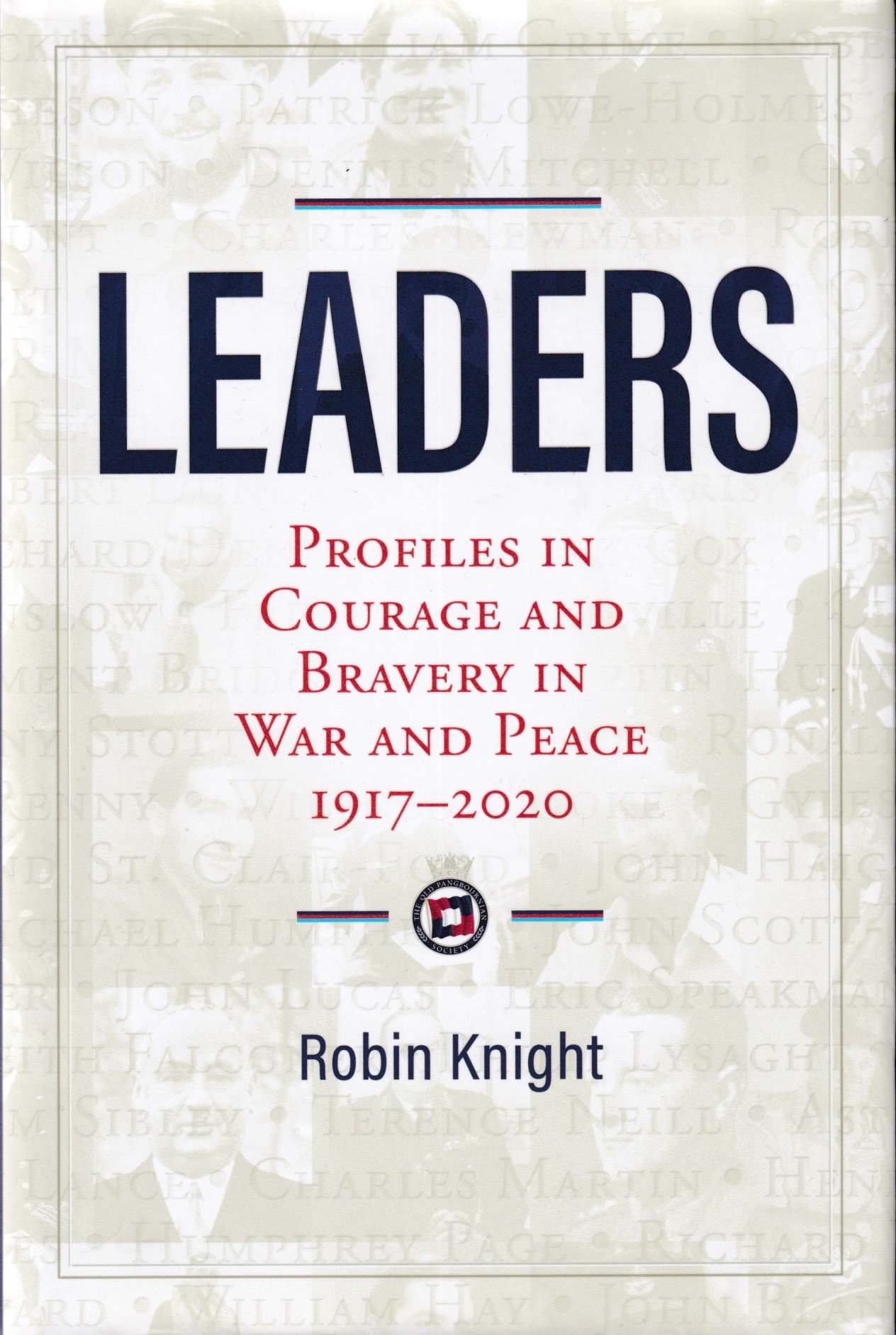

Leaders by Robin Knight

I was grateful to Robin Knight who wrote to draw my attention to two books of his which I’d overlooked when writing Uncommon Courage. This was both helpful and generous.

The first was his 2018 biography of the extraordinary yachtsman Mike Cumberledge SOE, who was murdered in Sachenhausen Concentration Camp early in 1945. This book remains a treat in store and I will certainly review it here at a later date.

This second book Leaders, published in 2021, caught my attention quickly as it offered additional information about three people who are included in Uncommon Courage.

The three are all Old Pangbournians - David Cobb, Jack Easton and Martin Johnson. Knight tells me, which I didn’t know , that I could have listened to Cobbs six hours of oral history given to the Imperial War Museum, digitally and remotely. That’s really helpful as I found the IWM pretty inaccessible researching during lockdown. In Cobb’s case I was fortunate to be put in touch with his daughter Mairet Rowe. That doesn’t mean I couldn’t have done both. Thank you for the research tip.

Knight’s information re Jack Easton GC I already had, but I was glad to know more about Martin Johnson GM. He wasn’t an RNV(S)R but worked closely with Ashe Lincoln, who was. He was Lincoln's colleague who disarmed the disabled German U-boat captured afloat and towed into Barrow in Aug. 1941. Johnson won a George Medal for this feat. Ashe Lincoln was not a trained torpedo dismantler as such and had to watch from about three feet away. (On other occasions eye-witnesses pay testimony to Ashe Lincoln’s ‘ice cold nerves’ as he too got hands on.)

Robin Knight’s book Leaders Is a valuable account of at least 300 individuals who went to the same school, the Nautical College Pangbourne, between 1917 – 2020. It’s admirable for its research assiduity and (usually) for avoiding too much Old School Tie-ism. There’s a refreshing paragraph where Knight discusses his decision to change the title away from the Pangbourne College motto ‘Fortiter ac Fideliter’ - despite the fact that all his ‘Leaders’ were OPs (Old Pangbournians). ‘At best it is a tenuous relationship […] Some of those featured in these pages did credit the school with developing aspects of their character, or skills, that aided them when they were called upon to act. The great majority did not. Far more important it was the context of the time that shaped those individuals.’

Knight insists that his book is not a glorification of war. ‘Instead it is meant to bear witness to gallant individuals and rescue their stories from the mists of time.’ I obviously concure with this aim and admire the thoroughness with which he has carried it out.

As well as the WW2 focus he includes some sporting success stories – and several accounts of service in the many ‘half-wars’ that characterised the second part of the c20th. His account of the Falklands war, from the insider perspectives of the Old Pangbournians involved, is particularly good

The Nautical College Pangbourne was established to train boys for the Merchant Navy. Every year is also made recommendations to the Royal Navy and saw boys set out on careers in flying or the army. There were no female pupils until 1996.

At the outset of the Second World War ‘virtually every OP, except for the medically unfit, served automatically in one of the armed services or in the Merchant Navy.’ The Nautical College was not a large school – about 200 pupils. The collective experience was not unlike some First World War schools where older boys and younger masters volunteered and were killed in droves.

‘Over the six years of the Second World War 178 Old Pangbournians are known to have been killed in action or died as the result of wounds or training accidents or in captivity – equivalent to an entire generation of cadets.’ By my calculation approximately half of them are named in the text of chapter 10 ‘The Supreme Sacrifice’. A clever balance is being struck between commemoration and narrative. The researcher may yearn for lists – though the index is good – but the general reader is kept interested and involved.

For specific RNVR research purposes there’s not very much direct information – cadets from the Nautical College tended to join the regular services or became part of the RNR. They usually seem to have been officers.

As a record of individual participation in the war at sea, I found it both readable and informative. This isn’t always an easy combination when so many names are to be mentioned but it’s helped here by the unobtrusively good production of the book. The names and dates of OPs in bold, there are small b&w photographs on many pages and two generous sections of inserted photographs, of which the more modern are rather shrewdly inserted before the earlier.

Robin Knight includes some reflections on various types of courage and perhaps distinguishes it from bravery. Winston Churchill’s ‘Fear is a reaction: courage is a decision’ is perhaps the most easily remembered summary. Generally, however, these accounts of experience spoke for themselves without needing any explicit link to moral values.

I recommend this book.